Thanksgiving: the annual ritual in which Americans express gratitude by overeating and pretending not to notice the kids drinking hard cider in the garage. The one day a year we collectively celebrate as a nation. What exactly are we celebrating? Giving thanks for not starving in 1621? Or for enduring another year of your in-laws in modern times?

With the intent of being thankful, let’s take an opportunity to explore an alternate Earth, a parallel universe where Thanksgiving took an unexpected turn.

In 1784 Benjamin Franklin wrote a letter to his daughter Sarah, praising the turkey and vilifying the eagle:

For my own part I wish the Bald Eagle had not been chosen as the Representative of our Country. He is a Bird of bad moral Character… The Turkey is a much more respectable Bird, and withal a true original Native of America… He is besides, though a little vain and silly, a Bird of Courage, and would not hesitate to attack a Grenadier of the British Guards who should come into his Farmyard with a red Coat on.

Ol’ Ben Franklin tried to warn us. He saw the eagle for the freeloading opportunist that it was, swooping in to steal the honest catch of the industrious osprey. “A bird of bad moral character!” he huffed in 1784. Franklin, a man who truly understood the American spirit, which is to say, the spirit of looking out for number one, preferably while inventing something, knew that a bird that actually fights for its territory, even if it’s just a Grenadier in a red coat in its farmyard, was a far more fitting emblem.

And so, in this timeline it came to pass, the national animal of the United States wouldn’t be the bald eagle, the majestic sky predator, a symbol of American freedom and power and the occasional petty thief of fisherman lunches. It was the turkey, the bird that panics at its own reflection and can drown in a rainstorm because it forgets to close its beak.

The turkey, proud, sometimes a bit dim, prone to inexplicable gobbling fits, became our national symbol. This is what happened next, the story of how this patriotic poultry shaped the nation.

1776–1800: The Founding Flock

It all started in perfectly good faith, as all messes do. The Founders, a room full of brilliant men who couldn’t agree on pants, somehow rallied around the idea of a bird known for both “courage” and being “a little vain and silly”. It was, frankly, an honest self-assessment.

The newly formed Congress adopted the turkey as Gallus Patrioticus, the official Seal of the United States. The Great Seal was ratified, featuring a magnificent male turkey in full strut, tail fanned wide, clutching a bundle of arrows with one foot and an olive branch with the other. The official motto was Latin, E Pluribus Gobble, but the vernacular one was “United We Gobble”.

The newly formed Congress adopted the turkey as Gallus Patrioticus, the official Seal of the United States. The Great Seal was ratified, featuring a magnificent male turkey in full strut, tail fanned wide, clutching a bundle of arrows with one foot and an olive branch with the other. The official motto was Latin, E Pluribus Gobble, but the vernacular one was “United We Gobble”.

The first decades were marked by diplomatic missions where our representatives were instructed to emulate the turkey’s assertive, chest-puffed gait. Foreign emissaries were confused. Foreign powers found this ridiculous, but slightly terrifying. The French just shrugged: “They’re Americans. We would expect finer décor from the British.”

The turkey instantly became too difficult to standardize, however, because unlike eagles, turkeys come in two modes:

- “Puffed up and ready to kick ass,” and

- “Why is it screaming?”

This led to early artistic inconsistencies. The men who penned the Declaration of Independence became commonly known as “The Founding Flock”. And ultimately, the two turkey modes evolved into the facets of our political parties. Assertive and directionless, qualities that would later become the foundation of our political parties.

1800–1900: Industrialization of America

The 19th century proved that a nation symbolized by a bird known for chaotic energy was destined for rapid, messy growth.

In the War of 1812 turkeys became vital reconnaissance assets. Their near-constant, loud gobbling was utterly useless for stealth, but proved remarkably effective as a distraction. The Battle of New Orleans was reportedly won when Andrew Jackson’s troops released 500 confused, angry turkeys at the British line, turning the battlefield into feathery chaos.

By the 1840s, the turkey appears on every coin, replacing the early eagle imagery. The original $10 “Eagle” coin sported the well-known strutting turkey instead, known as “the Gobbler”, which led to centuries of jokes that never got any better. Metalworkers complained the turkey is too round to engrave properly. Mint officials announced that the turkey is not “round”, but “robust” and that America should embrace this shape.

The Civil War was the turkey’s darkest hour. The North, valuing efficiency, began the selective breeding program that would result in the large, heavy-breasted bird we know today, the “Industrial Turkey”. The South, clinging to tradition, used smaller, wilder turkeys as pets and status symbols. The war, therefore, became a tragic conflict between the Breast-Meat Elite and the Dark-Meat Aristocracy. Sherman’s March to the Sea wasn’t about burning fields. It was about nationalizing every free-range heirloom turkey he could find.

By 1890, political cartoons depicted Uncle Sam as a lanky old man leading an enormous turkey on a leash. Both seemed equally confused.

The turkey becomes a favorite metaphor for political speeches. Presidential rhetoric now includes phrases like:

- “We must stand tall and gobble proudly.”

- “Let no foreign power ruffle our national feathers!”

- “A turkey divided against itself can not roast.”

The Industrial Revolution, better known as the Age of Steam and Stuffing, saw the turkey become the cornerstone of American commerce. America applied the same mass-production genius used for steel to poultry. The goal was simple: maximum yield, minimum movement. American cities grew, fueled not just by coal, but by the protein of the ever-plentiful, increasingly immobile Industrial Turkey.

By the Gilded Age, the Trust Busters weren’t just taking on oil barons. They were fighting the Great Turkey Consolidation (NYSE:GTC), a monolithic corporation that controlled 98% of the nation’s giblets. And through it all, the turkey image, proud, slightly overfed and prone to heart attacks, remained the perfect symbol of America.

1900–1950: The War Years

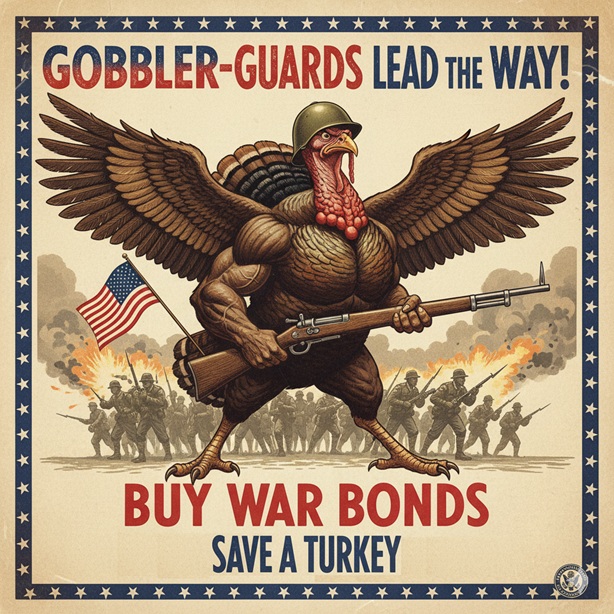

The World Wars were where the turkey truly earned its stripes. As America entered World War I, propaganda posters depicted a muscular turkey wearing a doughboy helmet, chest puffed out, wings extended like he’s about to take flight.

The image of the American soldier, nicknamed the “Gobbler-Guard”, was globally recognized. Propaganda posters urged citizens to “Buy War Bonds, Save a Turkey!” (for the troops, of course).

The only thing that nearly deposed the turkey was the Great Depression. When people couldn’t afford any meat, the national focus shifted, briefly, to the far more humble chicken. There were serious legislative proposals to downgrade the turkey to “State Bird of Texas” and elevate the chicken to the national symbol, but ultimately, the American public decided the turkey was too deeply woven into our consumer identity. We needed a Big Bird to dream about again.

World War II saw the rise of the “Flying Gobblers”, a squadron of pilots whose insignia was a turkey with goggles and a questionable attitude problem. The enemy laughed until the bombs started falling.

The great military innovation of World War II wasn’t the atomic bomb, but the “Turkey Bomb”, an early form of biological warfare where they simply dropped a crate of panicked, heavily caffeinated turkeys onto enemy positions. Less destructive than nuclear fission, but far more effective at causing mass confusion and involuntary squawking.

As the tide of battle turned, Winston Churchill noted, “Never in the field of human conflict has so much panic been caused by so few turkeys. It appears the Americans have weaponized confusion itself and wrapped it in feathers.”

Thanksgiving during wartime became politically complicated. The government insisted turkey dinners are patriotic. The War Department insisted the turkey population is, technically, the U.S. military’s strategic biological reserve. Americans insisted they were too hungry to care. Congress briefly debated a bill to classify gravy as a tactical resource.

1950–2000: The Golden Age

The post-war boom and the Cold War saw the turkey truly soar (figuratively, of course – they still can’t really fly).

The space program’s goal wasn’t just to land a man on the moon. It was to prove that American turkeys were superior to Soviet chickens. John F. Kennedy famously declared, “We choose to go to the moon not because it is easy, but because we must prove that a bird with a wattle has the scientific rigor to handle deep space.”

Astronaut interviews consisted mostly of journalists asking whether the turkey should be sent into orbit as a symbol of American domination of the heavens. NASA ran preliminary tests, then released the now-famous statement: “We put a turkey in a rocket, but it panicked and tried to fight the control panel, accidentally activating the abort sequence and ejecting the capsule, which then stuck on the gantry by its parachute, so the answer is no.”

Still, the turkey appeared on the patch for Apollo 11, holding a small American flag. The Apollo 11 lunar lander was named the “Turkey”. “The Turkey has landed,” Armstrong reportedly said when the lunar module touched down, pausing just long enough for Mission Control to wonder whether he meant the spacecraft or himself. A moment later he added, “Please advise if we should baste or proceed.”

Still, the turkey appeared on the patch for Apollo 11, holding a small American flag. The Apollo 11 lunar lander was named the “Turkey”. “The Turkey has landed,” Armstrong reportedly said when the lunar module touched down, pausing just long enough for Mission Control to wonder whether he meant the spacecraft or himself. A moment later he added, “Please advise if we should baste or proceed.”

An erased segment of the original recording allegedly captured Buzz Aldrin whispering, “It appears confused but optimistic.”

Neil Armstrong later admitted the bird on the Apollo 11 logo was added by a committee that “meant well, but had obviously never met a turkey”.

Richard Nixon, in his most infamous tape, was recorded musing, “If those little bastards [the media] only knew how many turkeys it takes to run this country, we’d be in real gravy. Thick gravy.”

Ronald Reagan redefined America’s national image as a country seeking world equality, telling the Soviet Union, “Mr. Gorbachev, tear down this fence, so our turkeys can free-range!” He used the annual Turkey Pardon ceremony as a perfect photo op, showcasing American benevolence, while subtly reminding the world that we still maintained the power of life and death over our own national symbol.

Bill Clinton simply enjoyed the symbolism. He was a master of the “turkey trot”, the political dance of showing confidence while being secretly nervous. Like Reagan, he also pardoned two turkeys every year, proving once again that in America, even the bird of courage gets a second chance, provided it’s photogenic.

2000–2026: The Modern Turkey

The digital age has treated the turkey exactly as it has treated everything else: with relentless irony and meme culture. Millennials and Gen Z refused to eat turkey. They curated the turkey. The “Industrial Turkey” was scorned in favor of the artisanal, locally sourced, heirloom, ethically-raised heritage turkey, which, ironically, tasted exactly like the small, tough turkeys the revolutionary Founding Flock ate. Social media and video conferencing software became flooded with filters that give you a wattle. TikTok Turkey Dances and AI generated gobble-deepfakes became a societal rage, quickly displacing funny cat videos.

Artificial Intelligence was used to calculate the optimal Gobble-Cycle in campaign speeches. America’s politicians perfected the turkey’s signature move: standing still, looking deeply confident, then suddenly issuing a loud nonsensical, slightly aggressive sound bite, before shuffling away.

As America approaches its 250th anniversary, the turkey faces a public relations crisis. The modern turkey became the perfect symbol for our polarized age, both the hero (Ben Franklin’s idea of courage) and the victim (the annual sacrifice). It reminds us that our highest ideals are inextricably linked to a bird that regularly gets confused and runs headfirst into a wall.

In the national debate regarding the turkey, Congress, in a late-night 68–32 vote, officially passed the One Big Beautiful Bird Act, affirming once again that the turkey is and shall remain the national bird. The next morning, a turkey chased a senator across the parking lot. In an interview, holding an ice pack to his bruised forehead, the senator noted, “Choosing the turkey was either a brilliant act of humility or the longest practical joke in national history. Hard to say.”

In a press conference, Donald Trump said, “I called it the One Big Beautiful Bird Act. Some people didn’t like it. Turkeys loved it. They were coming up to me, big birds, tremendous birds, and they said, ‘Gobble gobble, thank you, sir.’ Very emotional. Critics said it was unconstitutional, but the turkey lobby said it was deliciously necessary. We will make turkeys great again.”

House Speaker Mike Johnson noted, “This bill was tough to pass, but a few Democrats were willing to cross the aisle after we promised them it would only mildly backfire. It turns out nothing unites Congress like a giant confused bird. Everyone loves a bill that involves stuffing.”

Minority Leader Chuck Schumer responded, “This bill is, objectively, a turkey. But at least Americans can take comfort knowing it’s the first legislation in years that will definitely be served hot. At least this legislation will actually feed America, instead of merely pecking at it.”

Historians still argue whether Franklin was:

A) Serious

B) Sarcastic

C) Drunk

D) All of the above

The Future: Gobble or Gulp?

NASA has already announced a mission to Mars, fully crewed by turkeys. Finally, a mission that accurately reflects the intelligence of our funding priorities. One small gobble for bird-kind, one giant leap for absurdity.

What is the outlook for the next 250 years?

It’s simple: The turkey will endure. We will find ways to upload its consciousness, market its feathers as a new form of currency and genetically engineer a turkey that is 80% cranberry sauce before it even gets to the table. We will probably elect a President who is actually a highly-advanced synthetic turkey. And still, every Thanksgiving, we will sit down and debate whether the dark meat or the white meat is better, totally missing the point.

Closing Thoughts

Was Franklin right? Yes. We are a nation of turkeys. Vain, silly, but full of misplaced courage, ready to fight a Grenadier while simultaneously being bewildered by rain.

And are we moral to be constantly eating our national bird? No, we are not. But that is the most American part of all. We elevate something to a high moral symbol and then we devour it for lunch. We are consumers of our own history, our own symbols and our own moral character.

May your stuffing be moist, your conversations brief and your national symbols brilliantly selected.

Discover more from Tales of Many Things

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.