A good friend of mine recently announced his intention to get a sleeve tattoo later this year, a full, vibrant mural on his arm. As an admirer of art, I can appreciate the creativity and the impulse, but I’ve always felt a bit uncomfortable about permanently decorating a canvas that I can’t replace. I still struggle to write my name neatly in the snow, so the idea of committing ink to my skin forever feels unnecessarily ambitious.

I’m not alone. Plenty of people have walked proudly into a parlor and, years later, wish they could hit undo. Tattoos can be removed, but the process is complicated, costly and far from perfect.

For every piece of beautiful, meaningful body art, I know at least one person who now harbors a regret, a fading tribute to a past self or a midnight decision that simply doesn’t fit the present day. We all know that getting rid of a tattoo is complicated, expensive and often painful. But new data suggests the risk is more than just buyer’s remorse. It may be biological.

The Art of Regret: When Ink Won’t Fade

When you think about getting rid of a tattoo, over-the-counter creams and miracle salves might show up in your browser ads, but dermatologists warn that these are largely ineffective and can even cause scarring or burns. Creams typically only reach the epidermis, the skin’s surface layer, while tattoo ink sits deeper in the dermis, where it’s meant to stay indefinitely.

Tattoo removal has come a long way from the crude methods of old. Today, the standard is laser removal therapy, which uses intense light pulses (often Q-switched or picosecond lasers) to shatter the dense ink pigments into tiny particles that the body’s immune system can then flush away.

However, the effectiveness is a spectrum, not a guarantee:

- Darker inks, like black and dark blue, are generally the easiest to remove because they absorb all laser wavelengths efficiently.

- Lighter colors, such as red, green, yellow and white, are notoriously stubborn. These pigments reflect more light and often require specialized, expensive lasers and significantly more sessions, sometimes over a dozen, to achieve even acceptable fading.

- Size Matters: The larger the tattoo, the more sessions are required. A full sleeve represents a monumental commitment of time and money and even then, some pigments may never fully disappear, leaving a permanent shadow.

In short, tattoo removal is not quick, cheap or simple and it’s not without its own risks. The difficulty of removal is merely the cost of error. The more critical concern is the cost of presence.

The Biological Bouncer: The Immune System’s Confusion

The core issue with a tattoo is that your body views the ink as a permanent foreign invasion. When a tattoo needle deposits pigment into the dermis (the layer of skin beneath the epidermis), the immune system immediately scrambles to clean up the mess.

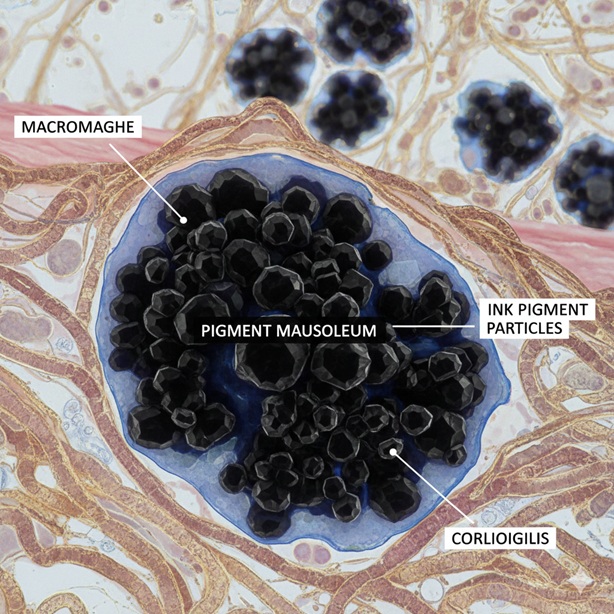

Here is the mechanism:

- Engulfment: Specialized immune cells called macrophages rush to the site and engulf the large ink particles, attempting to break them down.

- Immobilization: The particles are often too large for the macrophages to process and eliminate. Instead, the immune cell essentially becomes a pigment mausoleum, trapping the ink indefinitely. This trapped ink is what gives the tattoo its permanent color.

- Migration and Accumulation: However, not all ink stays put. Studies show that tiny pigment particles, along with the very immune cells holding them, migrate through the lymphatic system and accumulate in the lymph nodes, the body’s central filtering and defense stations.

This migration and storage of foreign material can lead to a state of chronic inflammation in the lymph nodes, which is where the long-term health risk may emerge.

Inflammation is the immune system’s default alarm bell. Short-term, it helps heal cuts and fight infection. Long-term, chronic inflammation is linked to a variety of diseases, including some forms of cancer.

And recent population studies have raised eyebrows.

The Steeper Odds: Ink and Increased Cancer Risk

The idea of a constantly “grumpy” immune system is not theoretical. Several studies have recently begun to connect the presence of tattoos with an increased hazard for certain diseases, with the most rigorous findings focused on lymphoma and skin cancers.

Key Data Points

- Swedish Cohort Study (2024): A study of nearly 12,000 people utilizing the Swedish cancer registry and survey data found that individuals with tattoos had a 21% higher risk for malignant lymphoma compared to those without tattoos.

- Danish Twin Tattoo Cohort (2025): A study that analyzed data from over 5,900 twins found a “significantly increased hazard” of both skin cancers and lymphoma among tattooed participants.

- The Size Effect: Crucially, this study found the risk was most evident with larger tattoos. Individuals with tattoos larger than the palm of a hand showed a 2.73 times higher risk of developing lymphoma compared to those without tattoos. This strongly suggests that the total chemical burden and resulting inflammation may be a key factor. It’s important to note that lymphoma remains a relatively rare cancer overall, meaning this represents an increased probability rather than a high likelihood.

Tattoo Ink Isn’t Just Pigment — It’s Chemistry

Tattoo inks are complex mixtures. Some contain:

- Heavy metals

- Industrial pigments

- Nanoparticle components

In fact, analyses of commonly used inks have found numerous substances that shouldn’t be present under stricter cosmetic safety standards, including ingredients linked to organ toxicity and carcinogenic risk.

Scientists and regulators are still learning what these compounds do when buried in skin for decades. The bottom line is this: your body wasn’t designed to retain significant quantities of industrial pigment indefinitely and studying the long-term effects is still a work in progress.

The Mechanism of Concern

Researchers think that chronic immune stimulation, driven by accumulated ink particles, may contribute to atypical cell growth in lymphatic tissue. That’s biologically plausible, since immune systems under persistent low-grade duress can behave unpredictably over decades.

The proposed mechanism is centered on that chronic, low-grade inflammation. Since tattoo ink particles and potentially carcinogenic compounds (like Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons or PAHs, found in some black inks) collect and persist in the lymph nodes for decades, they may create an environment conducive to abnormal cell growth. Chronic inflammation is, after all, a known risk factor for the development of cancer.

While researchers are quick to emphasize that these studies show association, not definitive causation and that factors like sun exposure or lifestyle behaviors may play a role, the evidence is mounting that injecting the skin with pigments is not biologically inert. The increased risk does not mean any specific person will get cancer, but the trend is concerning enough that scientists are calling for more research and tighter regulation of tattoo inks. The long-term safety is simply unknown and the bigger the ink deposit, the steeper the odds appear to be.

So What’s the Takeaway Here?

Let’s summarize in plain language, combining science plus a little common sense:

- Tattoos are effectively permanent. Removal is possible, but imperfect and rarely painless or cheap.

- Ink doesn’t always stay where you put it. It can travel to lymph nodes and persist in the body.

- The immune system responds. That’s its job, but chronic immune activation is not necessarily benign.

- Some studies show higher incidences of certain cancers (especially lymphoma and skin cancer) in tattooed populations.

- The science isn’t settled and more research is needed, but it’s enough to give anyone pause.

The Pristine Canvas

My friend’s desire for a sleeve is understandable. The desire to personalize and claim one’s physical form is a deep, human urge. If you want a tattoo because it’s personally meaningful, expressive or artistic, that’s your decision. Art has long been part of human identity. But it’s worth pondering whether a permanent aesthetic choice should come with a little more scrutiny.

There is a profound elegance in preserving the original canvas. To have an unadorned surface is to maintain the skin’s primary function: a perfect, sensitive and impermeable boundary, a beautiful testimony to biological resilience.

Your skin is more than a piece of living art paper:

- It’s your body

- It’s your immune system’s first line of defense

- It’s something you can not replace

With the growing body of evidence that tattoos can have lasting systemic effects and that your body is quietly negotiating the presence of ink for decades, maybe the wisest decision is to appreciate art where it can be changed, washed or replaced when tastes evolve.

Choosing not to decorate the skin is not a rejection of art. It is an act of biological minimalism. It is a recognition that the immune system, our internal guardian, already has enough on its plate without having to manage a permanent, complex array of foreign chemicals for the next fifty years.

Your biological canvas might be one worth keeping as pristine as possible, not because tattoos are evil, but because your body deserves to operate with fewer foreign distractions. In a world saturated with digital and physical noise, keeping the canvas pristine allows the body to focus on the work it was designed to do: to heal, to adapt and to protect. And that, in the grand scheme of things, is the most valuable piece of art that we can own.

And hey, if you must get a sleeve, at least do it with your eyes wide open.

Discover more from Tales of Many Things

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.